Recently, the Boar had another opportunity to create for a cause —a Texas style barbecue for a fundraiser at the First Tee of Central Arkansas. On the menu: four briskets, sixteen chickens, and eleven pounds of sausage.

Let’s focus on the brisket. Brisket is one of the toughest cuts of beef, but when cooked low and slow it is a tender delight. The end result should be a flavorful bark on the exterior of the brisket, a pink smoke ring, and a tender meaty interior.

Understanding the composition of a brisket is important. A full packer brisket actually includes two separate muscles. The flat thinner section is called “the flat.” It is the leanest portion of the brisket. The thicker end is called “the point” and has more fat content. (As we will discuss below the edges of the point are often used for a special treat called “burnt ends”).

The quality of brisket is important. For best results purchase choice, prime, or Waygu –do not purchase select or unknown quality. The fat marbling is key.

To prep the brisket, I like to trim the outer fat down to about a quarter of an inch. Typically, one side has a thick fat layer that requires quite a bit of trimming.

Following the lead of Aaron Franklin of Austin, Texas, I believe in simple seasoning: Kosher salt and fresh cracked black pepper. As you know from our steak posts (Gnaw-Worthy and Ike-Like), I believe in liberal amounts of salt and pepper —that is even more true for brisket. Remember, it is a big piece of meat and you are only seasoning the outside.

True Texas-style brisket is prepared on a smoker (for this event, I fired up “Your Honor”). Wood selection is important because if the smoke is too strong, it will impart an off flavor to the brisket given the long cook time. I prefer to use a combination of Oak and Pecan and maintain the smoker about 225 degrees for a long, slow cook —just let it sit a spell.

Though it is a controversial topic among brisket enthusiasts, I place mine on the smoker with the fat layer up. If you like disputes, google “brisket fat layer up or down.” (I’m a bit of a waffler on the subject as you will see later, I reverse course in the last stage of cooking).

It takes between four and five hours of smoke to develop the nice pink smoke ring on the outer edge of the brisket. I prefer to let the brisket smoke uninterrupted during that time period. Some folks like to baste every so often because the moisture enhances the smoke flavor —but if you do, limit it to once or twice because each time you open the smoker it stunts the cooking.

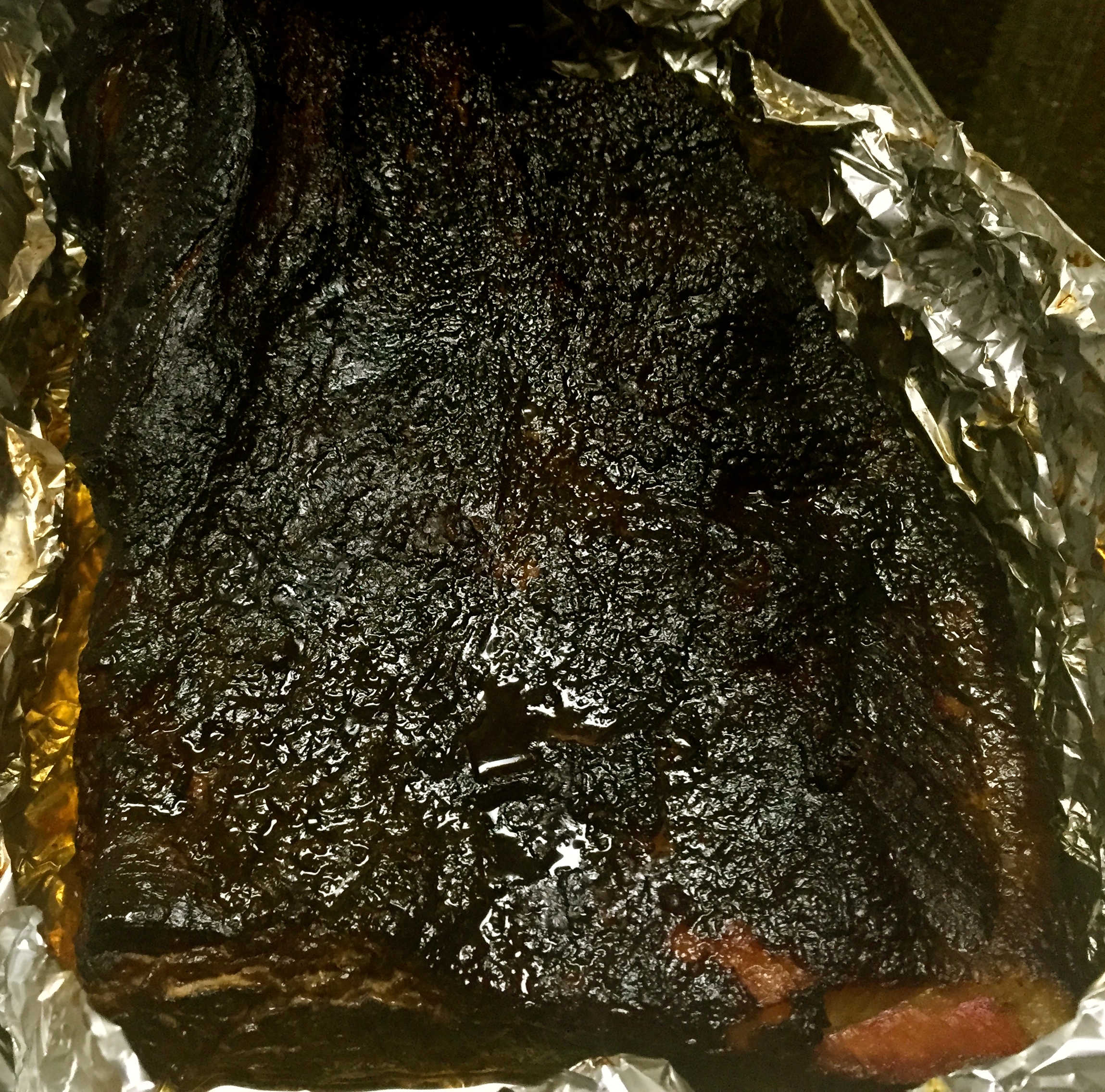

After the initial four to five hours of smoking, I like to wrap the brisket fully in foil. Wrapping serves two purposes: holds in moisture and speeds up cooking. I know that purists refer to wrapping in foil as using a crutch —but most competition cooks agree that it helps the process. One concern that I have with wrapping as it tends to make the bark a less crunchy —that can be remedied at the end by unwrapping it for the final stage of cooking.

Predicting the total cooking time for brisket is difficult because there are so many variables. I smoked these briskets for sixteen hours, but the determining factor is internal temperature. The sweet spot for brisket doneness is between 195 and 205 degrees —tender but not falling apart. It should be firm enough that you can make uniform slices and tender enough to pull apart at the slightest tug. (Note: you can tell when a brisket is undercooked because the chef will often slice it very thinly and when it is overcooked, the chef slices it thick).

Be aware of the stall! The internal temperature of a brisket will rise and rise and then all of a sudden stall for no apparent reason. Sometimes it can take considerable time to get the brisket to temperature. Be patient—maybe have a libation or two.

When the internal temperature reaches 195 degrees, I like to unwrap the brisket and increase the temperature in the smoker to about 300 degrees. This allows the brisket to cook a little further and also crisps up the bark. For this stage, I like to place the brisket on the smoker with the fat side down.

Brisket needs to rest when the cooking is complete (45 minutes to an hour is perfect).

The brisket should be sliced across the grain, and note that the grain for the flat and the point do not run the same. For a great lesson in slicing brisket google “Aaron Franklin slicing brisket.” As he demonstrates, the flat should be sliced about 1/4 inch thick and the point should be sliced about 3/8 inch thick. A large serrated knife works great for slicing brisket.

Now for a special treat —burnt ends (famous in Kansas City). Cut the edges of the point into big bite-size cubes.

Heat a small amount of oil in an iron skillet and sear the cubes until they are crisp. Braise in barbecue sauce and serve with a nice crusty bread.

Take it low and slow, my friend.